By Nqobizitha Dumakude Khumalo

LEST WE FORGET – Instalment 4

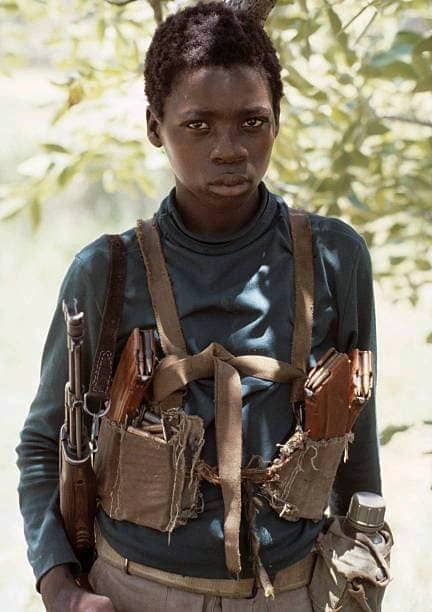

Comrade Chapungu Chehondo became a revered figure in Mberengwa—a legendary lone operator in the liberation struggle, whose daring exploits evoked comparisons to mythical spies and war heroes. He was, in the eyes of many, a living embodiment of Ian Fleming’s James Bond—except his war was real, his resolve unshakeable, and his mission national redemption.

Driven by fervent commitment to Zimbabwe’s independence, Chapungu—aptly nicknamed the Bateleur Eagle of the War—separated from his assigned unit and embarked on a solo campaign of sabotage and disruption. He cut power lines, laid mines, set vehicles and infrastructure ablaze, shelled enemy convoys, and ambushed Rhodesian patrols. His name alone instilled fear across enemy ranks in Mberengwa.

Chapungu moved between Chegato, Mnene, and Musume schools, as well as the surrounding hospitals. He frequently addressed students, teachers, and medical staff, steadily earning admiration and deep respect from the local populace.

While opinions about the guerrilla movement have grown more complex with time, there is little doubt that, overall, the fighters enjoyed significant support from the masses. Yes, coercion existed, and mistakes were made—inevitable in any armed struggle—but the people broadly identified with their cause. They believed the land rightfully belonged to them, stolen generations earlier by colonial settlers. The guerrillas spoke of justice and a better tomorrow, and the people listened.

Chapungu’s fame spread like wildfire. In the eyes of many, he was the action hero of his era—Tom Cruise, Arnold Schwarzenegger, John Travolta, and Sylvester Stallone rolled into one. The entirety of Mberengwa knew his name.

My nephew, then just a young boy admitted to Mnene Mission Hospital, never forgot the day Chapungu arrived. He had addressed the patients and hospital staff, leaving a lasting impression. He then sang a song that became a part of his legend:

Zanu Moto, Muchiiona

Zanu Moto, Muchiiona

Zanu Moto, Muchiiona makaitarisa muchiiona…Madhibha tabhana, Muchiiona

Mitero tabhana, Muchiiona

Zanu Moto, Muchiiona makaitarisa muchiiona…Chapungu waenda, Muchimuona

Hoyo waenda, Muchimuona makamutarisa…

It would be the last time my cousin saw him alive.

The Final Visit

Mnene Hospital was also home to the region’s first Black physician, Dr. Mushori Zhou. He and Chapungu had developed a relationship grounded in mutual respect and purpose. The doctor discreetly provided treatment and medicine to the fighter whenever needed.

In 1977, Chapungu sent word that he would address students at Chegato Secondary School. Excitement swept the institution. Students were cleaning the grounds when a tractor rumbled into the compound. Seated confidently at the wheel was Chapungu—armed with a bazooka and an AK-47, full of life and mission-focused.

The students cheered. A teacher, Mr. Nyoni, asked him to let the students complete their tasks while food was being prepared. Chapungu agreed but grew restless as the wait dragged on. The Assembly Hall quickly filled with students, teachers, and local residents who had heard of the upcoming address.

Climbing onto the podium, he captivated the room. He told of his early involvement in student protests and how he was arrested. He described how a grenade—hidden in a loaf of bread—was smuggled into jail, allowing him to blast his way to freedom. He evaded capture and reached Mozambique, where he underwent military training.

He compared the liberation war to the Biblical Exodus, casting guerrillas as modern-day Moses figures leading their people to Canaan. He paid homage to spiritual icons like Nehanda, Chaminuka, and Kaguvi. His eloquence and energy mesmerized his listeners.

For a moment, it felt like independence was just a breath away. But unknown to them, three years of bloodshed still lay ahead.

As Chapungu concluded his speech, Rhodesian soldiers entered the school from the eastern gate. The alarm was raised. In the chaos, he sprinted toward Dormitory 8, concealed his weapons under a pillow, and donned a school uniform.

When soldiers entered, he was calmly sipping a cup of sugared water—known in boarding schools as Koro. Locals confirmed he had been present but had since left. The soldiers believed the deception and departed, issuing stern warnings before leaving.

However, Chapungu had a fatal flaw: he often returned to familiar locations. Rhodesian intelligence had caught on. That night, he came back.

He held a pungwe in the girls’ dormitory, boasting of his escape and vowing to fight until Zimbabwe was free. The girls sang liberation songs, their voices echoing into the night.

Concerned, Headboy Chinyoka pleaded with Chapungu to allow students to rest. The freedom fighter appeared to agree.

Unbeknownst to them, Rhodesian soldiers had returned under cover of night and surrounded the school. One soldier, Leslie, entered the dormitory and gestured for silence. A girl spotted him and let out a quiet cry. The soldier motioned urgently, trying to clear a path to his target.

As Chapungu sensed danger and rose, a shot rang out. The bullet struck him in the forehead. He fell back—lifeless, weaponless. His body was riddled with more bullets. Girls screamed. Headboy Chinyoka was hit and later died due to delayed medical care. Another girl lost a finger.

The soldiers erupted in cruel celebration.

Desecration and Legacy

Chapungu’s body was paraded through the towns where he had once struck fear into the enemy. His lifeless, bloodied remains were tossed to the ground for people to see—an act meant to break spirits.

At Mnene Hospital, the soldiers mockingly summoned Dr. Zhou to “treat a patient.” Upon seeing Chapungu’s corpse, the doctor coldly responded, “I don’t treat the dead.” Days later, Dr. Zhou was assassinated under mysterious circumstances.

Chapungu was never officially buried. His resting place remains unknown. But Zimbabwe stands as his monument. The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at the National Heroes Acre is a tribute to fighters like him—whose blood nourished the roots of freedom.

On the night of 18 April 1980, the Union Jack was lowered and Zimbabwe’s flag hoisted for the first time. Bob Marley’s “Zimbabwe” and “Ambush in the Night” became the soundtrack of liberation.

Memory in the Wind

Many freedom fighters returned home—some wounded, others broken, many never again the same. Some did not return at all.

Mothers waited for sons who never arrived. Lovers yearned for embraces that never came. Childhood friends who once played under the sun waited for a reunion that would never be.

But Mberengwa did not forget.

At Danga, the ruins of a council building destroyed by Chapungu still stand. Inside, a sealed, heavy safe remains unopened. The keys disappeared with the officials who fled during the attack.

In the halls of Chegato, whispers of his ghost lingered long after. Though none could confirm it, none truly doubted it either. Chapungu died in body—but never in memory.

My late friend, Siyaphela Mangena, once urged that a plaque be erected in his honour or that Dormitory 8 bear his name. That recognition has yet to materialize, but the people still remember.

A school built by local villagers was first named Makwava Secondary before being renamed Chapungu High School in his memory.

Mr. Nyoni, the teacher who once hosted Chapungu, continued aiding the war effort, eventually gaining recognition from the ZANU Central Committee. After independence, he served as an ambassador.

Chapungu broke ranks because he believed the war wasn’t advancing quickly enough. His passion led him to take risks—some fatal. But such is often the nature of heroes.

Despite his mistakes, his zeal and determination ignited belief in the cause. His dramatic life—and death—motivated others to join the struggle.

We owe him—and others like him—a debt of gratitude. Their sacrifice paved the path to our freedom.

LEST WE FORGET.